Wit Capital

With all this IPO frenzy, small investors wanted in. By the time the institutional investors had scooped up the first shares, prices were often double. Good for them; not so good for the follow-on small investor. The proletariat were protesting this favoritism toward the bourgeois.

Wit Capital was an upstart on the financial block. Starting business in the Fall of ‘97, they had the idea of circumventing the usual IPO distribution — a process whereby only large institutional investors got a shot at the IPO. In a democratic assault on capitalism, Wit’s plan was to get a large allocation of shares, offering them in smaller blocks to its members. However, like a disliked cousin that had to be accommodated in the family, the i-bankers gave them a very limited allocation, or none at all.

Still, this seemed promising. I sent the initial $3,000 to start an account, or should I say, to ante up. I saw an email in March of ‘99 notifying me that a stock was about to go public, About.com. I felt the excitement of the game as I clicked to respond. There was a good deal of information about the company and a checkbox required to verify that one had read it. My first time at this, I looked over the prospectus. Actually, with 50 to 100 pages, I’d have to say I scanned it with less attention than a student reviewing the recommended reading list. Anyway, this was one of Doll Capital’s portfolio companies. Having dutifully affirmed that I’d “read” the material, I requested an allocation of stock at the IPO price.

Everything had been jumping from the initial offering price by multiples of two and three. Getting in at 15 when the stock closed the day at 35 would be a good day’s work. Beat the usual paycheck grind. However, the anticipated problem arose: Wit didn’t get much; the big boys at the table simply wouldn’t let them in. Ergo, I hadn’t been granted any shares due to “limited availability.” It was also ironic that I had gotten Itochu into a stock via a VC portfolio, only to be rebuffed at the chance to own some shares myself. About.com priced high at $25 a share and multiplied from there.

Other Wit IPOs came and went in the coming months: PLX, Flycast, Audible, ART, Mypoints, NetZero. I asked friends if they had invested in the IPO with Wit. Almost always the answer was negative: no allocations. This new democratization of the public market was failing. It was still a plutocracy of a limited set of institutional buyers. The i-bankers were holding stock tightly, divvying it up between large investors, friends and family, and to other executives of private companies they were courting.

After the market closed one afternoon in September, Wit emailed me again. Webstakes was going out the next morning; did I want in? At this point of disillusion, I didn’t even read the prospectus. I checked all the appropriate boxes and asked for shares. To my surprise, the next morning I was the proud owner of 100 shares, purchased at the IPO price of $14. At least I’d gotten in! The stock was up a few points, but not the meteoric rise I was expecting.

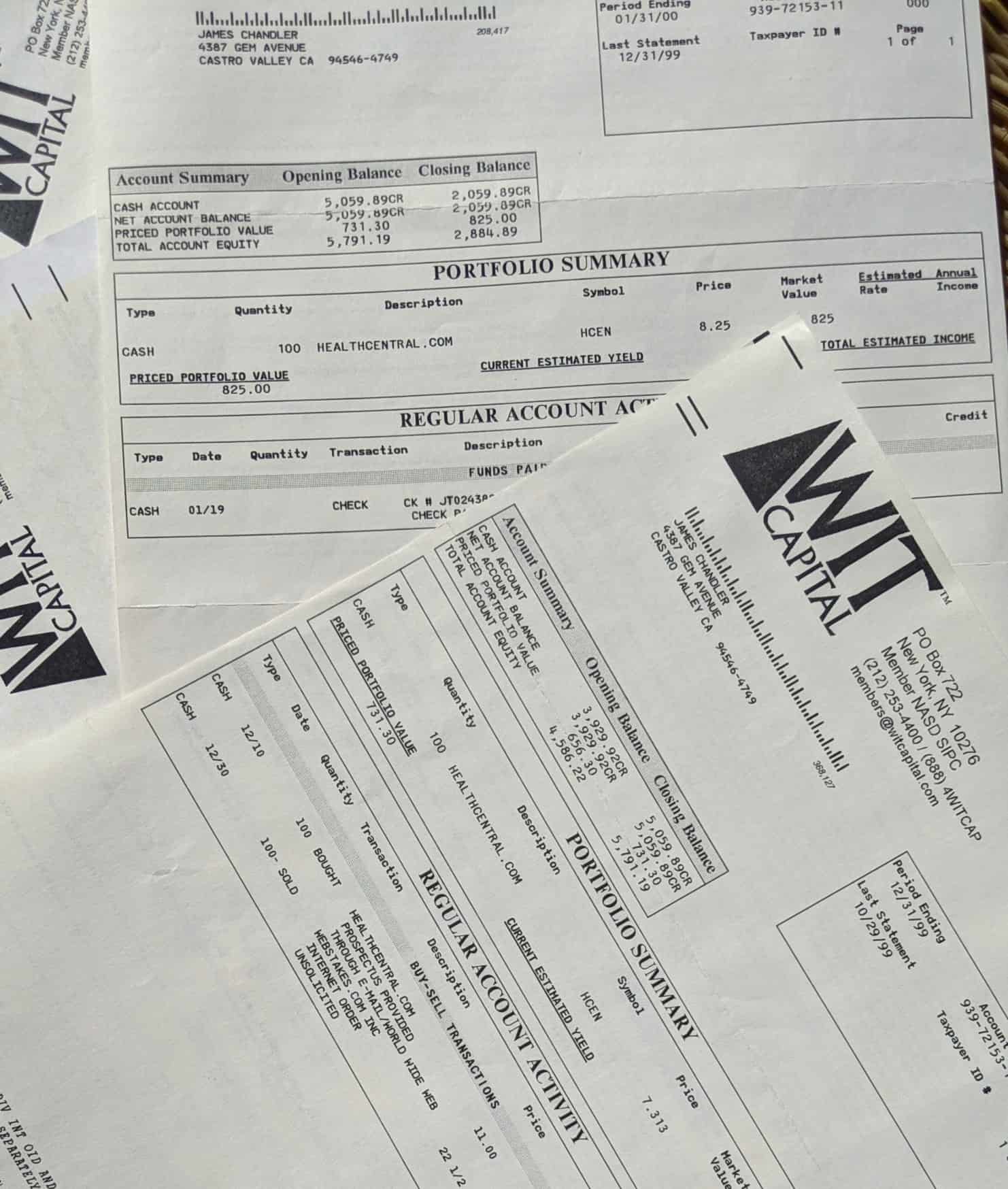

I pulled the one-armed bandit again in December, acquiring 100 shares of Healthcentral.com at $11. By this time, most tech offerings had a “.com” tacked onto the end of their names. Why were we getting shares all of a sudden? Was the market over-hyped? Were we getting the dregs that the professional money managers didn’t want? Wary, I decided to sell my Webstakes: price, $22 1/2; gain, $850 on a $1,400 investment; timeframe, three months.

This was a good return, but not the slingshot rise we had seen earlier. Was the market slowing down? Was there a shortage of sound companies after the valid prospects had rung the IPO bell on the NASDAQ? I didn’t have answers; I did have an uneasy feeling.

Leave a Reply