Winter Escape

Having arranged for my favorite perch aloft, I looked out the airplane window to see the northern coastline of Honshu, Japan’s main island, as it curved to an end. Hokkaido surfaced only a few miles further on. I tried to locate cities and towns but my geographic knowledge was lacking. Soon we turned inland, landing in Sapporo.

Cold weather, snow and ice on the streets, overcast skies – it all reminded me of my birthplace in winter. Yet I felt none of the depression that weighed me down in those forlorn months of my youth. For here was a new city, a culture open for exploration. With some difficulty I found the hotel Tomita-san had reserved for me. Small and straightforward, it had one tiny elevator to hoist me up six floors.

It took me forty-five minutes to call home from the hotel. Cable and Wireless, NTT/KDD, even the lobby pay phone refused my connection. Finally, with a phone card purchased from the clerk at $4 a minute, I reached home.

After talking with Annie for a midnight minute or two, she rousted my youngest daughter. When Chelsea came on the line, I could hear the affection in her voice, taking me back to the pre-teen years, when her Daddy was the most important man in her life. I felt her love as if she had jumped in my lap and wrapped her arms around me.

“I miss you, Daddy! I haven’t heard you in a week!” We talked about cheerleading and her latest track event: pole-vaulting. It was my old event from high school – probably the reason she tried it. Things had changed since the days of steel poles. Our three minutes went by quickly, our love clearly expressed. Talking to my daughter in California was the best ten dollars I’d spent in Japan.

The next day greeted me with peeks of sunshine as I headed out early, camera in hand. Still looking for the famed ice sculptures, I walked some of the shopping roads. I came upon a little park with old, wooden buildings – a wonderful contrast to the commercial steel and glass in the surrounding blocks. A blanket of fresh snow highlighted the rooftops and the tree limbs. Many smaller trees had little straw coats constructed around them. I recalled midwestern winters when my mother covered shrubs with straw to help them through the freezing months. Perhaps this was a similar but more stylized attempt. The skirts of straw were placed in very distinct layers, with a black belt of sorts tying them tightly on each tree. The dome of fresh snow on the top of each gave them the appearance of little people dressed in straw coats. A small creek ran through the park. I tried to capture some of this winter wonderland in the brightness between passing clouds.

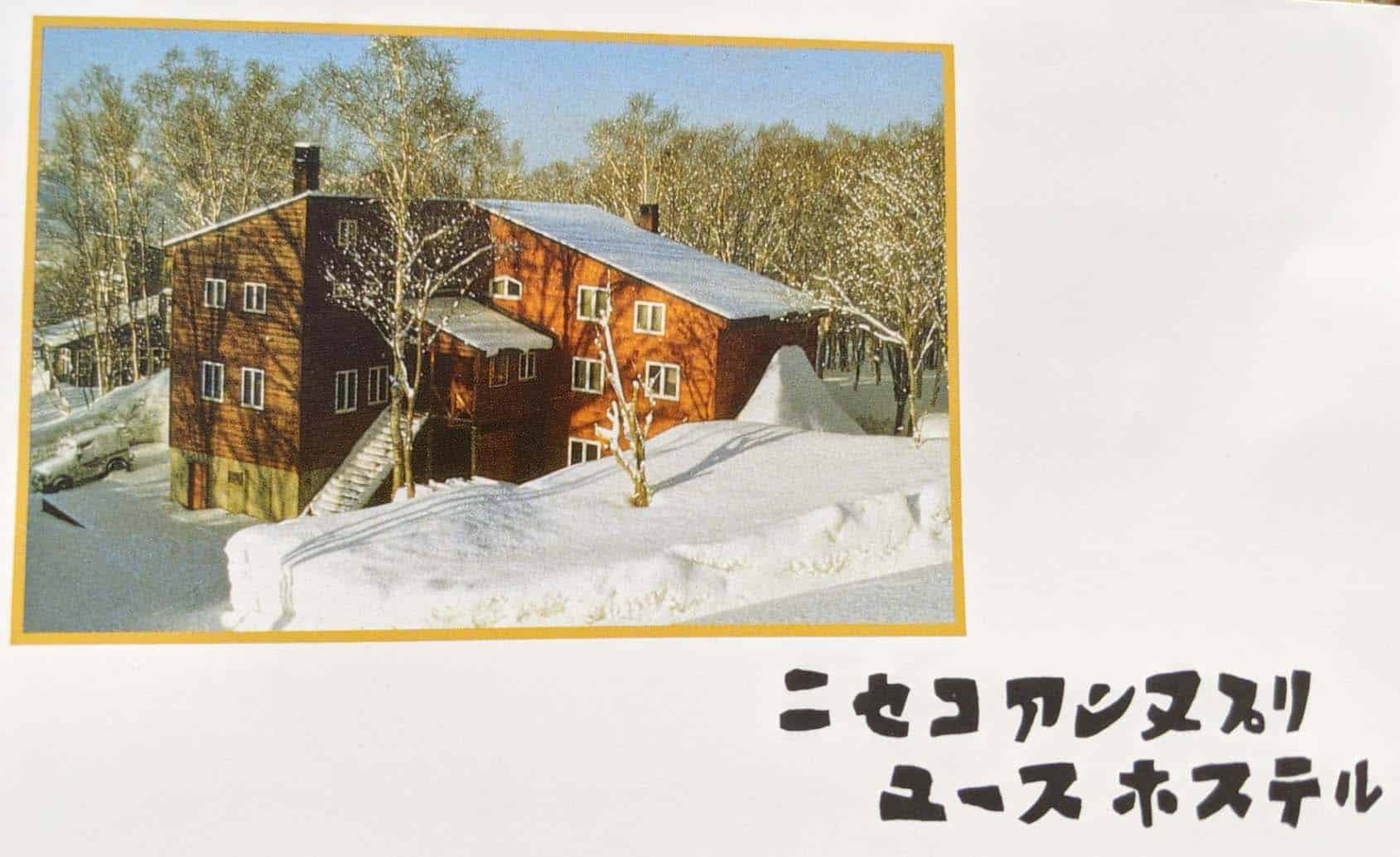

In a travel agency, I asked for information on Niseko. In broken English, a young woman offered assistance. Some of the brochures she handed me offered lodging with the train ticket. As long as I was backpacking, I thought it might be fun to stay in some sort of youth hostel. Okay, so I didn’t fit the “youth” part anymore; but I shared the world-inquiring spirit of the younger generation.

The young woman found a place in Niseko but was concerned that I could manage getting there, as few would be expected to know English. “How about Spanish?” I asked. She looked at me quizzically. I let the joke pass and suggested I would be fine. Could she call?

She arranged the reservation and gave me instructions to call the hostel when I arrived at the train station in Niseko. I thanked her and headed out once again into the overcast unknown.

I reflected on my increasing difficulty in traveling as I got further into the countryside. With all it’s strangeness, Tokyo was a piece of cake. Mind you, it was a far cry from traveling in Europe where Latin derivatives left you with a good guess at signs and maps. I longed to see some Romanji so I could at least pronounce what I could not understand.

I passed through a covered market, amazed at seeing so much seafood in one place — in new and unfamiliar forms! Fish swam in a huge circular tank I’d expect to see in an aquarium. These were surrounded by watery shelves full of scallops. Deep fried shrimp lay waiting like fast food, beckoning passersby to grab a tail and enjoy.

One stand had a half dozen different kinds of crab, most of which I’d never seen. I recognized the snow crab legs – much larger than I had seen. Others had bumpy shells or long thin legs that were doubled back under, reminding me of some kind of accordion. The young vendor saw me talking a picture. He lifted a live crab from a tank and posed.

I delighted in all this. It was like fantastic imagination wherein someone took a concept and expanded it, making up new forms: a natural, experimental artist. Yet these were all real. Why hadn’t I seen any of these crabs in the U.S.? Maybe crabs are a local thing: Dungeness from California, King from Alaska, and whatever these were from Hokkaido.

After a rest in my hotel, I hit the streets again to see the city of Sapporo in her evening dress. Cold as it was, there was a street vendor selling food from a brightly lit stand. Looking more closely, I could see this vending booth was actually a van with a pop-up top. He had opened the sliding door on the side to reveal a countertop, a stereo that was blasting and his smiling face behind an opening. I raised my camera as if to ask permission. He stuck his head out and grinned widely as I clicked the shutter.

I found one narrow street that seemed to run mid-block. It was full of little stalls, stores, and restaurants with neon signs. I looked over several, finally choosing one. Entering the door, I ducked my head inside. Soon I was seated at a table with two built-in ovens and benches on both sides.

Looking around, I saw people talking, smiling and enjoying their dinners. Searching for tips on how to proceed, I watched diners tending the grills in front of them. These were filled with fresh fish and shellfish. It was a mix between a Korean BBQ and Benihana without the chef. As I looked over the menu, which fortunately had pictures, a waiter came with a hot box of coals. He placed these in one of the ovens in front of me — a lined box built into the table. Replacing the grill top, he left me to look over the selections.

I was particularly interested in a neighbor’s crab leg medley. I found it on the menu and ordered the same. I wrote for a while as I waited. It was a comfortable place: it had the warm feel, the low ceilings of a dive, but the upbeat atmosphere of a good restaurant.

How often did Japanese actually dine alone? As I reflected on this, I recalled seeing individuals only at odd hours. During prime time lunches and dinners, there were only couples and groups. A socially engaged society, indeed.

Soon I was placing items from my delivered tray onto the grill: crab legs, fish, even a scallop that soon began to steam in its shell. Without peer, this seafood was the best I’d ever had! The grill gave the crab a smoky flavor so good I had no craving for the usual dunk in butter. I soon wished I’d ordered the crab alone!

Savoring the other seafood before me, I changed my mind as I finished. On the way out, I looked into the large oven where wood was being burned down to hot coals for the evening’s guests. I stood there for a minute or two, absorbing the radiant heat. Revitalized, I stepped into the cold night air.

At noon the next day I caught my train to Niseko. It was a pretty ride through forests and along the coast, the track running only meters from the water. I gathered there was no problem with heavy winds sweeping the water onto icy rails. I decided to break the ice with my seat partner, just opposite me. We’d been staring at or near each other for an hour and a half. In our collective knowledge of languages, we determined that he worked in agriculture, growing potatoes, beans and some other stuff that resisted our attempts to translate. He had two daughters, ages one and five. As he was about to detrain, I presented him with a gift for his five year old.

When packing for this trip, I had slipped in a little package of button covers I’d purchased years ago. My girls were now too big for these things, but they were so cute I could never toss them away. I liked seeing the little strawberries and apples that clipped over existing buttons – perfect for a small child’s sweater or overalls. Thinking I’d found a good place for them, I handed him the package and indicated a warning for his one year old not to put them in his mouth. He graciously accepted. It seemed a good thing for international relations, and particularly appropriate for a farmer’s children.

After a few hours we turned inland and headed up into the mountains. The countryside was beautiful and blanketed in snow. It was as if nature and man had worked out an agreement: nature was in command but man could pass as long as he stayed on a little track. Anything beyond was off limits. And so the train continued, gaining altitude.

Usually I can count the number of westerners I see in a day on one hand, using only one finger. Today I had to use two, as there was another American on the train. We never spoke directly but nonetheless felt an immediate bond – strangers together in the Japanese outback. We smiled at each other, then nodded in silent, mutual understanding. When he left the train, he looked back at me, smiled and waived. I returned both. A kindred spirit.

Darkness had descended when the train arrived in Niseko. Passengers headed to their cars, some meeting rides in front of the station. I found a phone and called the hostel. We didn’t communicate particularly well, but the fact that some English-speaking guy was calling from the train station was enough. I walked around the station as I waited.

The vending machines were always entertaining. There were so many ways of presenting coffee, tea and juice drinks. One machine puzzled me. In large bright English capitals the word ABOBA jumped out at me. Each letter was personified with eyes, eyebrows mouth. Amidst much Japanese script were also the English words “Just fit you and me.” Upon closer examination, I saw that the letters represented types of some kind. First I thought it had to do with blood type, as AB was grouped together in one product slot. O and A were also blood types. Finally it struck me and I burst out laughing. Condoms!

In my American experience, it had seemed funny that condoms were all one size. You could get ribbed, extra sensual thin, heavy duty rupture resistant, colored, flavored, plain or spermicided – but they were all one size. I had even thought up a comedy routine, in which guys bragged about needing the XXL version, or perhaps the Long & Tall size. Here before me was the suggestion that size or style varied a lot, or at least into four demographic sub-groups. I almost paid a thousand yen to purchase two and compare them. Laughing, I turned away, concluding that such evaluations were best left to the gender more qualified to so assess.

A few minutes later a van arrived. A middle aged man appeared and gestured toward the van. I guessed he was the manager; in any case, I felt no fear of abduction. Back to gestures and my twenty words, I communicated a little with the driver as we traveled to the hostel. He seemed to be the proprietor and said his name was Yoichi.

“Hai,” I began, trying to share the two languages. “Train station Yoichi.” I had recalled a station on the trip up here with the same name.

“Iie,” he told me no. “Station not same. That Yoichi. Me, Yo-ichi.” I could tell no difference except that he emphasized the first syllable. Okay then; another one right over my head!

Whether in Japan, Europe or the U.S., mountain architecture had a comforting familiarity for me. Even in the darkness, I could see the evergreens and the domiciles built for heavy snow loads. We arrived in front of a large wooden house with several distinct sections. I couldn’t make it all out in the dim light, but the craftsmanship and artistry rang out. We climbed up a long flight of steps to a door well above the snow level.

It seemed the driver was indeed the manager. Other people in the main hall, mostly young men and women, told me his name by pointing and saying “He is Oh-na.” I said hello to some of the travelers; it quickly became apparent that my Japanese was better than their English. Time to switch to gestures!

There was one American in this largely twenty-something crowd. As I settled in before a fire, I heard him laughing and talking with about eight Japanese guests. He seemed very fluent. After a while, we chatted.

Andrew had been in Japan about five years, first as a student. Now he was taking some time to travel. At present, he was staying here free — with an agreement to tutor the manager’s children in English. It sounded fun, though I knew he must be lonely at times — the fate of the single gaijin.

Tempted to feel a bit inferior to this young fellow, I soon reconsidered. He spoke Japanese and lived here for years. All this was easier for him. “So you come up here to the northern island of Japan, find your way to a small, very local ski resort and you don’t speak the language?” He eyed me curiously. “That’s pretty gutsy.” Or stupid, I had thought. Now I preferred to agree with him: it was bold. The lack of any other foreign visitor to the region seconded that opinion.

Oh-na showed me upstairs to a room with several beds. I gathered this to be my bunk for a couple of nights. Being once again in a youth hostel was invigorating, despite the obvious irony. The ski town environment and bunk bed atmosphere took me back to ski trips in high school and college. Tired from the traveling, I settled early to bed, anticipating the day of skiing to come.

In the morning, I noticed my only roommate was my fellow gaijin — apparently a practiced custom in Japan. The manager was right to place us together, assuming correctly I would benefit from his language and local knowledge. At breakfast, Andrew told me that a rental van came by each morning if I needed equipment. Soon enough I found myself riding up a chairlift in a very foreign skiing destination.

It was funny to see the maps of the runs and signs here and there in Japanese script. “We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto!” I laughed aloud. Nor California, Colorado, or the French Alps. Yet the runs were not so different from Aspen or Heavenly, and gravity worked the same. At the top of Niseko, on the side of the mountain called Hirafu, I began to ski … or rather, to ride.

The morning hours were sunny and the snow was good. My Panasonic micro-cassette player from Akihabara played the Allman Brothers as I glided over moguls and into open stretches. The slopes required no translation; I was in my element.

Later in the afternoon the skies turned overcast, visibility fell and light snow swirled down. I headed for the mid-mountain chalet. The only English words I saw were on a sign outside a building: “Restrant New Sanko.”

Neither there nor on the mountain did I see any gaijin. I was the lone representative of foreign lands — ignored but tolerated. The few times I asked someone to take my picture were met with friendly cooperation. It was strange for everyone to have me there. I was clearly out of place; yet I had become accustomed to this. I headed out onto the runs for the rest of the afternoon.

I arrived back at the hostel pleasantly tired. The manager, Oh-na, served us an excellent dinner. Curious, I asked my American translator if that was a common Japanese name. He didn’t think so but asked the other men at the table. They pointed to the large room and said, “He is Oh-na.” Okay, I finally got it: he’s the owner of the hostel!

After dinner, I noticed two pillows near the sofa with brightly colored helicopters and English words. Curious, I bent down to read. One said, “Flying Game. A very comfortable day seems to be starting.” The other began the same but continued, “With songs sung by birds, I can greet a comfortable morning.” Definitely not Kansas.

Andrew and I talked for a while about experiences in Japan, recounting some silly moments and eventually landing on English misspellings. I mentioned the “Restrant” I’d seen today, and added the street sign in Tokyo advertising “Lanch,” followed by a long list of Japanese food items. His favorite was better.

“I saw a young Japanese woman, aspiring to urban chic. She had high boots, six inch soles – which meant eight inch heels. She wore a fashionably cut shirt with a sunflower on it. The words on the shirt read: ‘Sweat Smell.’”

“So much for sweet,” I concluded.

I woke early in the morning. My inner clock was still screwed up, despite the time I’d spent in Japan. Outside my window I could see a blanket of freshly fallen snow, beckoning. Andrew was still sleeping. I dressed quietly and went downstairs. No one was up. I took a few things with me and went outside with my camera.

A winter wonderland greeted me. Strange houses made it even more magical. The sun was out with only a few clouds occasionally blocking its brilliance. The cold air kept the snow fresh and crisp. Sunlight reflected off icicles that hung from unusual rooftops. I walked past Bed & Breakfast-like houses with funny names or logos. One had “Frying Pan” as its name and logo: two words in English! Other names were spelled out in English as well as Japanese. Capping a multi-gabled tower on one inn was a huge hat of snow and ice, frozen and melted many times to give it layers and an odd shape, like a cocked baker’s hat.

No one was out as I snapped pictures. Boney James played Kyoto on my slender tape player. Jazz in my ears, sun glinting into my eyes, snow crunching underfoot, I traversed an unfamiliar fairyland. It was enchanting!

Back at the hostel, I had some breakfast and went up to my room. Andrew was groggy but awake. “It’s a beautiful morning outside,” I said in earnest. I told him of my walk. The response I saw in his sleepy eyes was one I had seen many times, a passing curiosity about what I would find so interesting about such a simple thing. It was my Zen: hard to explain without sharing the experience.

“You have months to be here, to enjoy this place. I have only this day left, this glimpse. I want to take it all in.” My words didn’t make much sense to him at this hour in his day.

I took my leave of this friendly hostel and walked to a nearby bus stop. Oh-na had told me the time and general location for the buses going to the JR station. Yet I knew there were shuttles that ran to the other side of the mountain. I considered my situation. I was here, at the stop, all set for an easy connection. Or I could catch a shuttle and check out new territory. They would probably also have bus service to the JR station. I could see more. After all, isn’t the idea to push a bit, to extend the experience?

Yes, to a degree. Here I am, in a mountainous region of the northern island of a foreign land. Other than Japanese locals and tourists, there are a few Aussies around somewhere and no one else who speaks English. You don’t speak the language, Jim, and can’t read the signs. You know you are further than a walk to the train station. Your flight leaves tomorrow from another city … and it’s snowing hard. You’re out there, Jim. You’ve pushed it. ‘Nuf already!

As I returned to the train station, I saw yellow snow plow engines waiting on the tracks. In the middle of the two front windows were circles, probably for venting, morphing into large circular eyes of a mechanical creature. A painted rainbow spilled down each side.

Once underway, the train took us through beautiful stretches of wilderness. I snapped pictures on the curves where I could see clear views or catch a section of the train in motion. We passed old cabins that reminded me of the Lincoln Log style of construction. The train broke upon the coast and scooted the shoreline. I gazed over the vast expanse of water. Maybe it was growing up on a lake in Minnesota, maybe just Pisces rising – but I loved to see a stretch of open water with the sun playing on the waves.

Leave a Reply